The C program build tool flow includes

- source files (.c, .h) which are compiled into object files (.o)

- assmebly files (.s) which are assembled into object files (.o)

- library files (.lib)

All of these are linked into memory into an executable file (.exe, .axf).

Assembly Files

In assembly files, sections of (binary) instructions can be referred to using memory addresses which, in the assembly file, are called labels. In the assembled object file, the main memory locations point to each label in the assembly file.

Importantly, the label main will be available to other object files during linking. When you have an instruction using a non-main label like LDR R0, -hex_number, the assembler precomputes the offset so that other object files cannot use that label.

Files with a .h extension are header files and are included in .c files. The convention is for them to have the same name, and they get compiled into one object file. Before, the C files are compiled, the header files are literally copied and pasted into the top of the C files that include those header files.

If you have a linking error, it could mean there are two functions with the same name or there is no implementation of an expected function.

The header function can be thought of as containing function prototypes, which include the function name, arguments names and types, and return type.

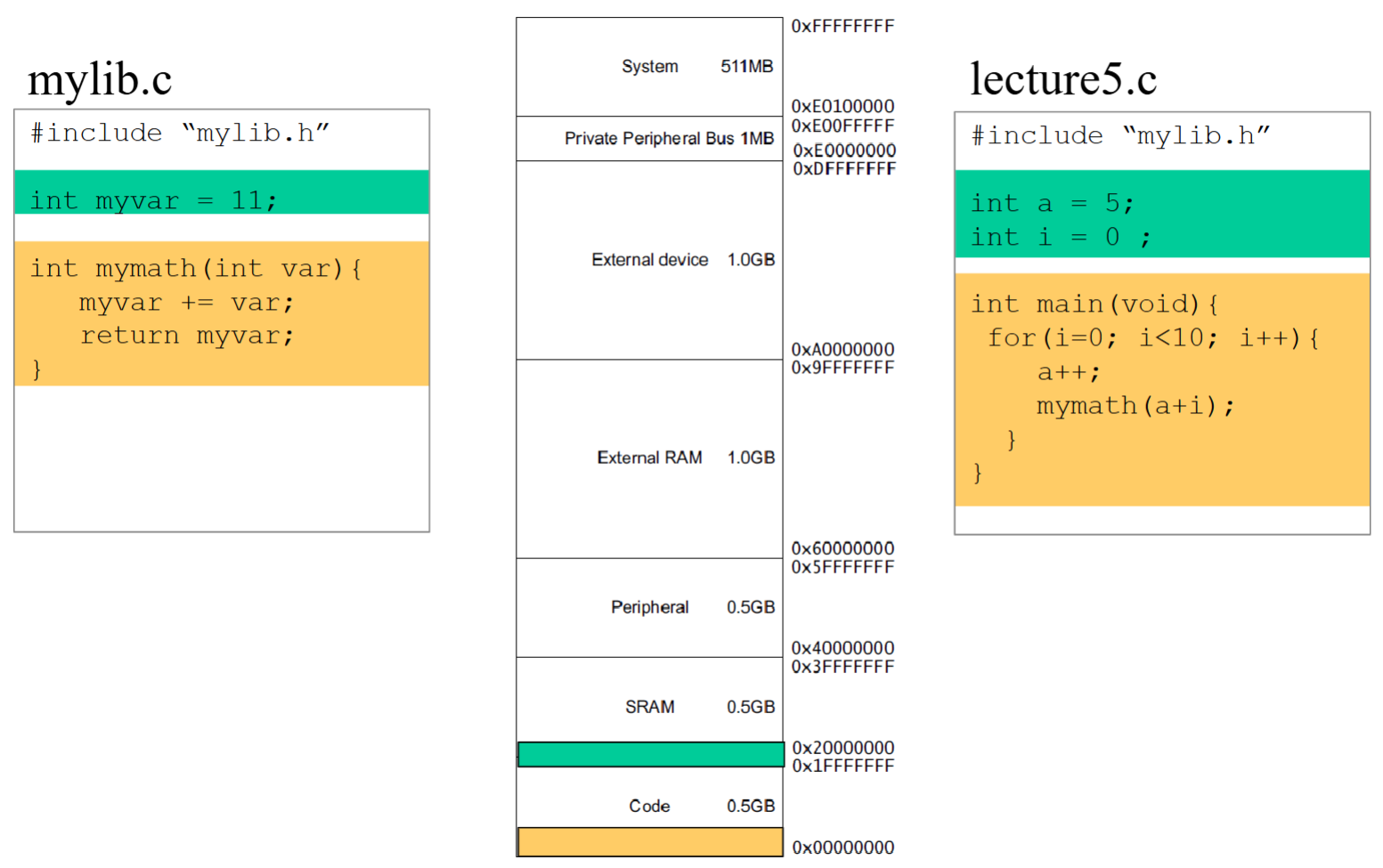

When a C file (or compilation unit) is compiled, the object file should have labels for each function and variable. However, by default, labels for non-main functions in C files can not be referred to by other C files. Therefore, you must advertise that something is accessible to other files. This is done like so: extern int myvar;. It is usually put in the header file. Accordingly, you cannot make another variable with the same name as an externed variable or else the linker will get upset.

Recall our memory map. Since SRAM is cheaper to manipulate, variables get addresses allocated in the SRAM section (or mostly in the SRAM section). The code then gets memory allocated in the flash memory.

Implementing Control Flows

How would you implement an if-then-else block in assembly? This is done by having if, thn1, els1, thn2, els2, and end blocks. This is what an unoptimized C compiler does.

Another control flow is the the switch control flow which compares a value to multiple values and a default value. This is done by using labels for each case as well as an end label. This makes it apparent why case blocks need break; statements. Using the switch control flow is easier to read because each case depends on the same variable or expression, and it can be implemented more efficiently in assembly.

A for loop can implemented with for, next, and end labels. Inside the next block, we use a condition which is the opposite of the loop condition that points to the end block. Note that adding the counting register and comparing takes more clock cycles than inititializing the counter to #NUM and subtracting one because subtraction automatically sets the condition flags.

Function Calls

A C program consists of at least one function, which can also be called a subroutine. A function can take arguments and can return a result. Functions are useful because we can reuse code and make programs more modular. A subroutine should be callable from different program locations and should support nested/recursive calls.

How does a function receive parameters? Do we give it a register or a memory location?

We can have a corresponding assembly block for the caller (s = func(1,2,3)) in which we move immediately values into registers and then branch to the func label. Then, inside the assembly code that corresponds to the func implementation, we can do calcaulations with the registers that were just set.

We can simply set the return address to R0, but hard-coding the return address doesn’t work when you want to call another function inside the original function. To solve this problem, we can use the ADR instruction which can compute and store the return address in the link register when we return then branch back to the function which called the function.

However, there is an instruction called BL that does all of this in one swoop which makes calling functions very easy like so: BL func. We still need to use BX LR to return, but the link register holds the address of the most recently called function, which can cause an infinite loop with multiple functions.

To fix this problem, we use stacks.

Stacks

A stack is a last-in first-out data structure, and the stack pointer points to the last item on the stack. The stack grows toward smaller addresses. Stacks has pop and push operations.

The stack pointer points to words, so its last two bits should be 0. We can implement PUSH {R4} by first decrementing the stack pointer then storing the register: SUB SP, SP, #4, STR R4, [SP, #0].

In ARM, we can PUSH and POP multiple registers to a register. Also, we can use POP {PC}, which pops a stack and branches to that address.

ARM vs. Thumb Mode

ARM code works in 32-bit instruction mode while thumb code is largely in 16- bit instruction mode. It is possible to wrap code from different modes within each other, and we call this interworking.

As a result, if we branch into a different mode, we want the processor to be able to change modes. If we manipulate the PC register and the last bit is 1, then the processor knows to execute in thumb mode. We don’t lose information by doing this because all addresses are even anyway.