Inference Rules

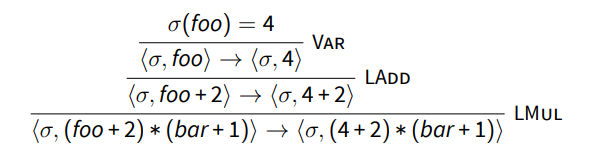

Suppose that $\sigma$ is some store that maps foo to 4. Consider $\langle \sigma, (\texttt{foo} + 2) \times (\texttt{bar} + 1)\rangle$. In this case, the only inference rule that applies here is the one that allows the left side of the product to take a step. Doing this repeatedly results in a proof tree which shows how we can go from the original configuration to the “final” configuration:

Note that we conventionally say that there is only one step from the original configuration to the evaluated configuration since the “substeps” only help us navigate to the final configuration. To do this, we define a multi-step relation, written $\rightarrow^*$. With $\rightarrow^*$, we can step with reflexive and transitive closure:

$$\frac{}{\langle\sigma, e\rangle \rightarrow^* \langle \sigma, e\rangle} \text{REFL}, \quad \frac{\langle \sigma, e\rangle \rightarrow \langle \sigma^\prime, e^\prime \rangle \quad \langle \sigma^\prime, e^\prime\rangle \rightarrow^* \langle \sigma^{\prime\prime}, e^{\prime\prime}\rangle}{\langle \sigma, e\rangle \rightarrow^* \langle \sigma^{\prime\prime}, e^{\prime\prime}\rangle} \text{TRANS}.$$

One can prove that something is in the reflexive relation if and only if it is in the transitive relation (not sure if he actually said this).

Properties

There are several properties a semantics could have that are provable by induction:

- Determinism: Every configuration has at most one successor.

- Termination: Evaluation of every expression terminates.

- Soundness: Evaluation of every expression yields an integer.

Our arithmetic language satisfies the first determinism and termination, but if it gets stuck with unbound variables, it may not satisfy soundness.

Therefore, we might be interested in restricting ourselves to well-formed configurations $\langle \sigma, e\rangle$, where all the free variables that $e$ refers to have values in $\sigma$.

$$\begin{aligned} fvs(x) &\triangleq \{x\} \\ fvs(n) &\triangleq \{\} \\ fvs(e_1 + e_2) &\triangleq fvs(e_1) \cup fvs(e_2) \\ fvs(e_1 * e_2) &\triangleq fvs(e_1) \cup fvs(e_2) \\ fvs(x := e_1 ; e_2) &\triangleq fvs(e_1) \cup fvs(e_2) \setminus \{x\} \\ \end{aligned}$$

If we have a well-formed configuration, we can formulate two properties that imply soundness:

- Progress: there is always a step that that can be taken

- Preservation: every step preserves well-formedness

Inductive Sets

An inductively-defined set $A$ is one that can be described using a finite collection of inference rules. For a rule

$$\frac{a_1 \in A \quad \cdots \quad a_n \in A}{a \in A},$$

if $a_1, \dots a_n \in A$, then $a \in A$.

If there are no premises, then the conclusion is an axiom.

The small-step evaluation relation we just defined, $\rightarrow$, is an inductive set.

Now, note that every BNF grammar defines an inductive set. However, we use BNF grammars because they are more concise.

To write the natural numbers as an inductive set, we may write the following:

$$\frac{}{0 \in \mathbb{N}} \quad \frac{n \in \mathbb{N}}{succ(n) \in \mathbb{N}}.$$

We may revisit inductive proofs from the world of inductive sets. We may do inductive proofs on the way an inductive set steps or on the actual structure of $e$. They may b esimilar, but sometimes one is easier than the other.

To actually do the proof, if we have a property $P$, we should prove it on the axioms as well as for each inference rule (proving that if $P$ holds for each premise, then it holds for the conclusion).

We can prove progress by structural induction on $e$.

Here is a proof outline for proving progress on any expression $e$ in our arithmetic example.

We have five rules to prove the property for.

For

$$\frac{}{x \in \text{Exp}},$$

for any $\sigma$, assume $wf(\sigma, e)$ (wf means well-founded). Therefore, $fvs(x) = \{x\} \subseteq \text{dom}(\sigma)$.

Then, by the $\text{Var}$ rule, for any $n$, we if $\sigma(x) = n$, we can step from $\langle \sigma, e\rangle$ can step to $\langle \sigma, n\rangle$, which means there exists $ \sigma^\prime, e^\prime$ such that $\langle \sigma, e\rangle \to \langle \sigma^\prime, e^\prime\rangle$.